In its sustainability plan published at the end of 2019, Formula 1 management detailed how much emissions all operations cause and made commitments at all scales, listing the steps already taken towards the goal of net zero by 2030. So how much carbon emissions does Formula 1 produce as a sporting organisation? What is being done to reduce the emissions, and beyond that, to have a positive impact?

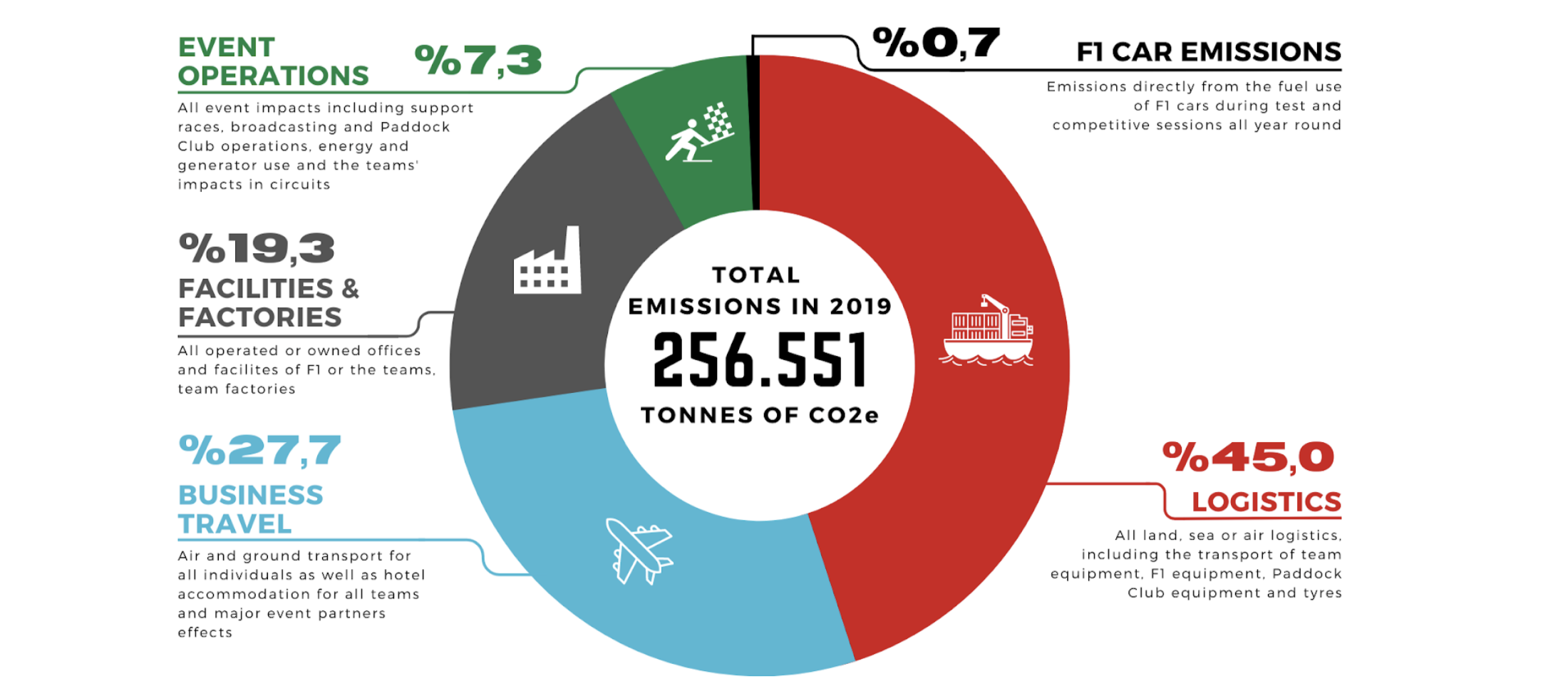

According to the published report, 256,551 tonnes of carbon emissions were estimated to be caused during the 2019 season – equivalent to the yearly use of almost 56 thousand cars. However, the breakdown of these emissions is a bit surprising. While we think of Formula 1 cars as gas guzzling machines, they are the source of only 0.7 percent of total emissions and the share of other operations within the sport is much larger.

Click here to read the blog post on the steps taken to reduce the emissions of Formula 1 cars.

RACE WEEKENDS

According to data collected in 2019, event operations accounted for 7.3% of total emissions. The main change in this area was the relocation of the facilities used for broadcasts to a fixed location. The broadcast facility, which travelled the world with the teams and was set up on the tracks at each race prior to Covid-19, has been halved in size, while a facility in the UK has started to be used to continue broadcasting activities remotely. It is said that the cargo travelling from race to race has also been reduced by ⅓ thanks to the portable facility being halved in size.

Formula One management has announced that from 2021, staff working at race events will not use single-use PET bottles during the event and will use reusable bottles for drinking water instead. The aim is to completely eliminate the use of single-use bottles by 2025. It was also announced that the paddock entrance cards used by the team and organisation personnel will be made from recycled PET bottles.

There have also been some changes in terms of tyres to reduce emissions on race weekends. All cars are currently allocated 13 sets of tyres each race, but as part of a transition to lower this number, allocating 11 sets to cars will be trialled in two of the 23 races in 2023.

The use of electric heating blankets – used to keep the tyres at optimum temperatures for competition – is also being gradually reduced. Whereas previously 10 sets of tyres were allowed to be heated to 100 degrees, five sets have been allowed to be kept at 70 degrees since 2022. In addition, the time allowed for having these blankets on the tyres has been reduced from 3 hours to 2 hours from 2023 onwards.

However, the fact that the FIA has specifically asked the tyre supplier to design tyres that wear out and lose performance in a short time shows that there is potentially still a long way to go in this area. By using far fewer tyres in races and working on alternative methods to keep the excitement at a similar level, the number of tyres produced and travelled around the world for the sport in a year can be reduced from over 25 thousand to a much lower number.

TEAM FACILITIES AND FACTORIES

Teams are also taking steps to reduce emissions, particularly in their factories. These include sourcing their electricity from renewable energy sources, harvesting heat from production processes to heat the facilities and reducing the amount of waste going to landfill down to zero.

Although Formula 1 management has pledged to use net-zero technologies for electricity and heating systems from renewable energy at team facilities, which account for 19.3 percent of emissions, the majority of emissions at these facilities come from R&D and manufacturing work.

LOGISTICS AND STAFF TRAVEL

DHL, the logistics sponsor of Formula 1, announced that 120 thousand kilometres were travelled during the 2021 season – equivalent to 3 trips around the world. The transport of all cargo – including car parts, team equipment and tyres – accounts for 45% of the 256 thousand tonnes of emissions generated during the season. The transport of personnel to and from the races on the calendar is also a considerable source of emissions – with all air and land travel and hotel accommodations for team, sponsor and organisation staff accounting for 27.7% of total emissions.

It was pointed out in the sustainability plan that a new, lower-emission aircraft fleet or shipping options by sea are being evaluated in order to reduce these emissions in logistics operations, and that trees will be planted as compensation for unavoidable emissions.

However, while taking these measures, it is necessary to bear in mind the increase in the number of races in the calendar. Since ¾ of the emissions stem from the organisation travelling from country to country, and even from continent to continent throughout the year, the increase in the number of races on the calendar raises some question marks. While 20 years ago the number of races in a season was 16, this figure has increased to 19 ten years ago and to 23 today. The rapid increase in the number of races in a season against the commitments made to reduce emissions constitutes a significant contradiction in this regard.

All these efforts mentioned are limited to minimising the negative environmental impact of all Formula 1 operations. However, as many studies support, social impact and environmental impact are intertwined, and both need to be addressed together to maximise impact. With Formula 1, the International Automobile Federation has taken some initiatives to increase the participation of women in the very male-dominated field that is motorsports.

As a solution to the lack of female drivers progressing through the levels of motorsport, a women-only racing series called the W Series was created in 2019. The series was short-lived with it being cancelled midway through its fourth season in 2022. Now, another series called the F1 Academy, which has a similar structure, will run from the 2023 season. Many prominent figures in the world of motorsport have stated that these racing series have achieved the opposite of what was intended by completely separating female drivers from their male counterparts, and that it would be much more effective to use the funds for programmes that support female drivers from a young age instead of these competitions.

In terms of team staff ratios, the initiative seems to be left to the teams. The Alpine team, which has taken the most concrete steps in this context, have shared that 12% of its 850 employees are women, and that it aims to bring this ratio to 30% by 2027. They also added that they aim to have an equal number of women and men join their team through internships and graduate placements. Finally, they announced that they will identify talented young female drivers at karting level and support them as they advance their motorsport careers.

As with many organisations’ sustainability plans announced under the banner of ‘Net Zero by 2030’, Formula 1’s impressive commitments should be treated with a grain of salt. While these pledges are extremely ambitious and do a good job in making people more aware of the pressing issues we face, reading between the lines, it is possible to see that these commitments and measures already taken may not be as beneficial as they are said to be. In order to really achieve these goals, or even get closer to them, we need to adopt a systems change by changing our mindset beyond the changes made in the current system.

READ MORE: Formula 1’s Sustainable Fuel Solution